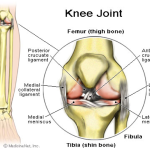

The knee is a hinge joint, the largest of its kind in the body. It garners much of its support from internal and external ligaments and has relatively less support from bony approximations. There is a large degree of flexion/extension at the joint but very minimal medial or lateral rotation can occur without high risk of injury to the collateral ligaments. The cruciate ligaments prevent forward and backward glide of the femur on the tibia and also provide rotational stability. The menisci are formed by cartilage which provide cushioning and help transfer force.

Respecting the mechanics of the joint is paramount to keeping the knees healthy. Gray Cook and Mike Boyle’s “Joint by Joint Approach” does this. This approach emphasizes the knee’s need for stability to ensure optimal functioning. As long as the knee has a normal range of motion, training should focus on keeping it stable.

The joints of our body, however, do not work in isolation. Therefore, we need to consider the whole system when training. For ideal knee motion we need good joint integrity at the hip, ankle and foot, as it is very much an interdependent relationship. From this point we can begin to train the lower body: good training for the knee is good training for the hip, ankle and foot. It would be remiss of me not to mention the importance of total core stability here as our extremities rely heavily on the foundation of a strong core.

Many, if not most of us have experienced knee pain or injury, personally I have had a few. While impact injuries oftentimes cannot be avoided, overuse, poor use and non-contact injuries can be dramatically reduced with smart training.

Another often overlooked component to knee pain, chronic or acute, is myofascial tissue quality (Bennett 2007). Muscle and fascial restrictions in many regions of the leg can manifest in pain at the knee, such is the interconnected nature of the body. I have addressed chronic knee pain with clients through the introduction of simple self-myofascial techniques using foam rollers and other implements, often leading to the resolution of symptoms. It can be a simple as this sometimes but many find this hard to believe and think something more sinister must be at play than a tight muscle.

That said, the reasons these restrictions often occur in the first place usually lie in the movement strategies people adopt, or in many instances from a sheer lack of movement. While the myofascial component is an important one to address, oftentimes it is merely a symptom and not the underlying cause. That is why good movement practice is so important, in either maintaining joint integrity or regaining it.

In my opinion, weakness is a big culprit in musculoskeletal pain, both in terms of a lack of muscular strength and endurance. Again I think this can often be overlooked. The joints in our bodies are supported by muscles, tendons and ligaments. If they are not strong enough to support the joint, it stands to reason there will be dysfunction. This is especially true for the inactive (use it or lose it) the overweight, ( 300lbs is hard on the knees for sure) and the senior population, (we atrophy as we age).

Training the knee (lower body)

When thinking specifically about the knee, we can use the anti-movement approach we use for core training. While we want the knee to flex and extend, we simultaneously want to limit rotation. Therefore, when performing strength training exercises, we can think about tracking the knee with the middle toe. Similarly, with more dynamic exercise, when rotation is involved, we can practice the rotation occurring at the hip and thoracic spine and not the lower back or knees. “Practice makes permanent.”

In training the knee there also needs to be intelligent progression that respects the existing mobility, stability and strength of the respective structures involved in lower body locomotion. While there are many intricacies and variables to consider in designing a program, the following are some guidelines to consider in terms of progressive strength training or indeed in rehabilitation from injury.

-Master the sagittal plane first. It is also a good idea to start with bilateral stance before progressing to split and single leg stance. Examples of this would be deadlifting, squatting and bridging before lunging and single-leg work.

-Have control of static positions before attempting more dynamic variations. If one cannot stabilize in a half-kneeling stance, it is unwise to try to move dynamically in and out of that position as in a split-squat or lunge. Equally, if one cannot do a solid split-squat, lunging should not be included until the less dynamic motion is better controlled.

-Integrate the frontal and transverse planes for more functional carryover. In life and sport we do not move exclusively in the sagittal plane. We therefore need to train the frontal and transverse planes to prepare for the dynamic nature and eventualities of life and sport.

– Balance in training. Endeavour for balance in all aspects of training. Train all functional movement patterns and strive for mastery. If you are participating in a sport that is asymmetrical in nature, attempt to balance this with an opposing pattern either in the gym or on the training field.

Closing thoughts

Working in the fitness industry in both private and public gyms for over 7 years, I have seen many crazy and injurious acts. Sometimes perpetrated by trusted professionals. I once witnessed a physio instruct a client, who was recovering from his 2nd ACL reconstruction, to jump one footed laterally, on and off a bosu ball. This is not intelligent training for anyone, least not that poor guy. My only hope for him is he gets a discount on surgery no. 3.

The point I am making is, to train stability at the knee and the lower body in general, progressive and quality movement practice, that respects how we are intended to move is best practice, not gimmicky unstable surface training. Eric Cressey, of Cressey Sports Performance, wrote a great article reviewing unstable surface training for T-Nation for anyone interested in further reading.